Rob Larson | April 21, 2022

As Covid restrictions continue to wind down in the U.S., many of us are re-emerging after years spent living online. Some of us likely have rusty conversational skills, even to the point of borderline feral social graces. And with an upcoming midterm election, when tempers already run high, we may be in for a year of, well… less than incredibly enlightened political discourse.

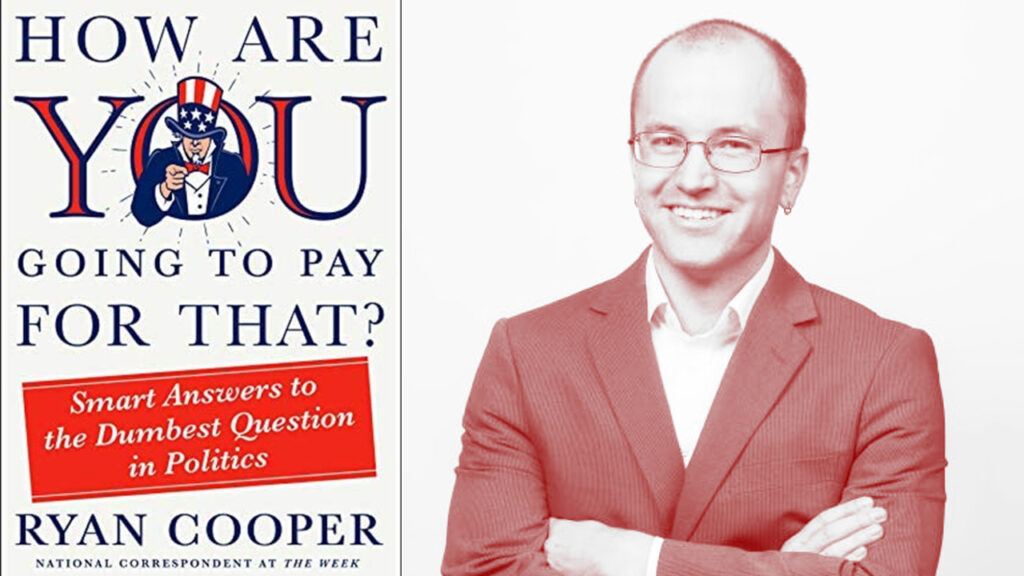

Thank the risen Lord, then, for Ryan Cooper’s 2022 book How Are You Going to Pay for That? Smart Answers to the Dumbest Questions in Politics, a one-volume education in contemporary politics and economics that’s just the thing for those awkward political exchanges with coworkers and needlessly intense conversations with conservative family members. Cooper’s book is a surprisingly effective way to expose a conservative know-it-all or liberal naïf to a sensible, progressive worldview, and it’s enjoyable to boot—despite certain ugly prejudices that mar the text, as we’ll see below.

Thinking in Trillions

As a teacher and professor of economics, I can confidently say that what Cooper’s book accomplishes is no mean feat. It is a very readable blend of economic concepts, political history, and policy prescriptions, written for someone without much familiarity with any of these things. Cooper opens with a discussion of “savings scolds” like Ann Coulter and Dave Ramsey, who reliably blame America’s economic problems on individual failings and lack of initiative. For the root cause of poverty and economic sluggishness, look no further than their favorite culprit: the hordes of insufficiently thrifty, latte-sipping millennials. Meanwhile, both political parties incessantly bemoan the bloated federal debt, intone about the unfortunate need for more austerity, and somehow manage to reach across the aisle to shoot down the most moderate spending bills.

But then a devastating pandemic breaks out in the U.S. in 2019, and shit gets real. The entire political-economic machine, which normally can’t muster the will to secure comprehensive medical insurance for penniless children, suddenly couldn’t care less about how we’re going to pay for that. Indeed, to date, the federal government has spent nearly $5 trillion on Covid relief. This strongly suggests that the abiding political concern about “affordability” is less than sincere.

From here, Cooper launches into a meticulous deconstruction of mainstream paranoia about “spending” and mounts a bold case for establishing social democracy in America. Cooper skillfully summarizes enough history and policy for the average reader to follow the plot without getting bogged down in technicalities, and adeptly explains the rise of our current economic regime. It’s a world that runs on reduced taxes for corporations and the ultrawealthy, a featherlight regulatory touch, rampant privatization, and increasing precarity—something many have come to call “neoliberalism.” Cooper shows how our neoliberal reality was created through strategic lobbying and election spending, in an attempt to move the Overton Window toward seeing the chaotic market economy as a pure, “self-regulating machine.” For Cooper, terms like these, which already favor libertarian ideas, are wildly misleading; instead, he refers to free-market ideology as “propertarianism.” It’s kind of awkward, but as someone who’s written book-length refutations of libertarianism myself, I definitely sympathize.

Propertarian notions suffuse American life so thoroughly we barely notice them, but Cooper holds a penetrating lamp to our cultivated ideological fog, demonstrating the immense burdens it places on Americans. From young parents who delay having children because of the crushing costs of care, to college kids who select majors based on mere earning potentials, to the forced choice many face between bankruptcy and basic medical care, propertarianism constrains life choices and cons us into seeing economic hardship as a personal—rather than systemic—failure.

Unlike many books on economics, Cooper brings us back to the origins of capitalism to explain the hegemonic power of propertarian ideology. It becomes clear that capitalism itself is responsible for ideology of propertarianism, a distorted vision of society that bows to the dictum that “owners of property should exercise political command over society.” Cooper takes us on a breezy but informative tour through the enclosure movement that birthed capitalism, as well as the tremendous state support for early industrial capitalism in the form of direct subsidies, fat tariffs, and a well-funded police force to discipline the working class. We learn too about the constant battles between capitalists and workers, in which bosses tried to reduce the working class to a mere “factor” of production, alongside impersonal raw materials and machinery.

To explain the dry economic phenomena of propertarianism, Cooper uses popular public policies and issues—the stinginess of Social Security (especially Disability Insurance), hated tech monopolies, and the endless new fees imposed by deregulated airline conglomerates. Even the Gold Standard is made a lot more gripping in the context of today’s towering financial asset bubbles and crashes. He contrasts the “propertarian” argument that markets are self-regulating with a better-evidenced “collective economics” based on the reality of our mutual interdependence, and the fact that markets universally rely on government support and coordination. Indeed, the very meaning of “owning” something is often reducible to who has the state’s official recognition as owning it.

The history of economic thought is another area where Cooper’s skills shine, and the reader gets very clear explanations of econ concepts bolstered by simple examples—nothing extra fancy added. His treatment is not at all shallow, though, and Cooper includes his own quantitative economic analysis, sprinkled with some legit original graphics. Splitting the difference between technical rigor and a writing style that is intelligible to the lay reader is no easy balancing act, but Cooper does it with clear historical knowledge and rich imagery.

Waste of Nations

Since his book is all about affording things, Cooper is naturally interested in the utter waste of economic resources and human potential in the U.S. Contemporary capitalism provides us with plenty of examples of promiscuous resource waste, from thousand-dollar bottles of wine for the wealthy, to millions of unused Covid vaccines bought up by rich countries, to personal space programs for out of touch billionaires. Wasted human effort is a conspicuous feature of American capitalism, too. The monumental financial crises of 2007-2009 rewarded the culprits with huge bailouts but caused a giant recession that spoiled the human potential of millions of American workers. Cooper is especially irritated by the outrageous number of work hours that Americans expend compared to their peer nations, all due to “recent policy choices.” In Denmark, a far less powerful country than the U.S., workers get an additional ten weeks of paid time off relative to the average U.S. worker.

Above all Cooper is focused on the godforsaken waste of time and money represented by “The Hell of American Healthcare”—an entirely apt description. America is notorious for spending trillions of dollars more on health care than other peer countries, and yet it consistently achieves shittier results, with U.S. life expectancy steadily declining over the last five years. Cooper observes, “that enormous mountain range of money is not buying us access to care when we need it,” an incontestable fact: 45% of Americans who earn below-median incomes say they have skipped recommended medical care, and an incredible 32% of those with above-median incomes have done the same.

Cooper carefully traces this waste back to higher doctor pay and completely crackers prices for hospital/clinic care and pharmaceuticals—mainstays of private health care that require constant, desperate measures to keep them afloat, from preferential tax treatment to mediocre Obamacare. One of the book’s best moments comes when Cooper exposes the naked lie used by defenders of the existing privatized health system; namely, that unlike with Medicare for All, you can keep your current doctor and coverage. Lies! People lose their coverage the moment they get laid off, fired or change jobs. Cooper cites a University of Michigan study which found that, at the end of just one year, only 72% of people in their survey sample were on the same employer insurance plan they enrolled in at the beginning of the year.

Cooper compares failed privatized solutions to Senator Bernie Sanders’ proposal for phasing in Medicare for All by age cohorts, bringing a few ten million people into the program each year until universal coverage is reached. Cooper observes that the number of people who would be switched to Medicare under this Radical Collectivist Plan is around 38 million each year—fewer than the number forced to switch private coverage in normal conditions. As Cooper concludes, “We can’t afford not to have Medicare-for-all.”

Helping the Rich Man into Heaven

To put his case for social democracy in context, Cooper clearly outlines the different social supports enjoyed by “developed” nations in North America, Europe, and East Asia. Most on the Left will be bitterly familiar with the relatively luxurious welfare systems maintained by social democratic countries that are no richer than the U.S. Looking to these models, Cooper argues that we can and must fund sick leave, family leave, free education, public health care, and a whole lot more. In addition to endorsing Left policy goals like Matt Bruenig’s Family Fun Pack, Cooper contributes novel ideas of his own. He proposes a Jobs Office in every U.S. town and city, as well as a new Public Works Administration that keeps a large standing library of national engineering projects to pull from more heavily in bust times.

But the real challenge to Cooper’s agenda is posed in the book’s title. As public figures and pundits reliably demand, how will such an aggressive policy agenda be paid for? Surprisingly, it takes Cooper until page 167 to face this question head-on, and even then, he is slightly coy, suggesting that the program will be paid for with tax revenue, while admitting he’s “not qualified to specify exactly which taxes should be raised.” I would have appreciated just a little more detail on which basic tax categories could be leveraged. A progressive income tax with certain top rates and thresholds? An estate tax above so many millions of dollars? Taxes on the daily multitude of destabilizing financial transactions? He does, however, produce a full estimate of the cost of Medicare for All, estimating a per-person tax (pre-progressive structure) of $2,500 a year—much less than a year’s paycheck deductions under current conditions.

And to Cooper’s credit, there’s no pretense that we can pay for it all just by soaking the rich, though this will be a big source of revenue for any expansive public financing plan. Indeed, slightly higher taxes on the majority of taxpayers would be essential to rolling out a social democratic program in the U.S., since redistributing money downward is inflationary. The question posed by the book’s title “implies that the cost is going to be painful. But the real pain comes from failing to set up” social democracy. “We all pay in the form of more stressful, shorter, less healthy lives that are devoured by pointlessly huge amounts of work.”

Bottom line, Cooper’s book is a very convincing presentation of how a full social democratic program could improve our lives and how it could be afforded. There are, however, a few weak points and oversights. It only occasionally brings up the “s” word: socialism, which accords with his goal to convince the indifferent or skeptic. The sections discussing the history of economic thought are mostly John Maynard Keynes and only a dash of Karl Marx—for better or worse. Marx easily divides crowds and a lot of socialists are overly excited by his ideas and their legacy. Since the book is focused on practical coalition-building goals it mostly invokes socialism to describe a broad, enduring strain of leftist ideas.

But this does lead to some problems in his analysis. Cooper (recognizing it’s a very big “if”) claims that “if there are a reasonable number of competitors in a market, and companies can set their own prices, and the population of consumers has a relatively equal amount of income…then a market is a perfectly functional way to distribute things.” But this perspective is still very compatible with huge global entities owning immense capital and wielding outsize influence over society and politics. Most socialists argue, instead, that leaving large-scale capital in private hands, as in the highly-taxed and regulated New Deal era, is precisely what keeps economic power in the hands of an international class of affluent large-scale property owners—the same class that launched the neoliberal “propertarian” assault in the first place. It is understandable that Cooper tries to avoid intra-left debates. Naturally, it’s not something to dwell on in a book that aims to convince a wide variety of people of a progressive worldview.

Further, given how carefully Cooper projects costs and locates trillions in inefficiencies, it’s amazing that he never once takes up the most insanely costly, over-resourced, and bloated arm of America’s public sector: the U.S. military. In addition to the world-bestriding colossus of the Pentagon, the security-related arms of the departments of Homeland Security and Energy (which runs the nuclear weapons program), as well as the CIA and black budget, come to a total well north of a trillion dollars every godforsaken fiscal year.

The political asks of a social democratic program are already significant, and redistributing money through deep military cuts could have limited popularity. But for a book organized around the question of how to pay for the left’s desperately-needed and super-cool programs for universal health care and climate action, it’s a little surprising that the military-industrial complex’s trillion-a-year doesn’t even surface. In the context of the Russo-Ukrainian war, this may represent good political instincts on Cooper’s part. But considering the book’s rich treatment of nearly all of the American economy, it’s a head-scratching omission.

The Biased

I must now pause for a moment and comment on a rather ugly feature of Cooper’s book, which mars an otherwise valuable and readable text. While Cooper may try to deny it, he is clearly guilty of relentless hate speech in this book, mostly directed against economists. Cooper has a naked prejudice against me and my proud colleagues, based purely on our persistent wrongness and the large proportion of our guilt we bear for the world’s enormous problems. Apparently selling out the human race and dooming the world for thirty pieces of silver makes us “The Bad Guy.”

Cooper’s unhinged rants are full of outrageous claims that challenge basic truths of my profession, such as “There are no…economic laws, of course. There are guidelines, rules of thumb, and constraints, but no ironclad deterministic laws…contingency, human agency, and planning.” He suggests that my field has an “airless culture,” insisting that we base everything on models built on laughable assumptions about nice, small-business-based markets and kind-hearted capitalists who’d never think of polluting the environment. While this may be true, it is offensive.

Cooper’s smear campaign against economists continues as he takes up a giant of the field, Friedrich Hayek, and the Austrian School he’s associated with, calling them “a lot more honest” than their American colleagues. What could he mean? Cooper quotes the highly influential Austrian economist Ludwig von Mises, who supported a “putsch” against democratic governments, as well as his colleague Hayek, who told a Pinochet-era journalist, “a dictatorship may be a necessary system for a transitional period… Personally I prefer a liberal [pro-market] dictator to democratic government lacking liberalism.” Far from being distant examples, this hostility among economists toward democracy echos directly into the present; for instance, when Germany’s finance minister told Greece, a country toying with the idea of rejecting austerity economics, “Elections cannot be allowed to change economic policy.”

Worst of all, Cooper claims that “[a] whole generation of economics grad students were trained like circus seals to guffaw on cue” when anyone suggests that capitalism may be flawed. This sort of hate speech against my profession is almost enough to destroy the book’s credibility—unless you too, Reader, harbor some irrational animus against economists, perhaps because of our track record of providing cover for Koch brother rule, justifying relentless corporate mergers, and rationalizing climate death. Well, excuse us for living!

In spite of Cooper’s utterly unprovoked attack on my noble and selfless profession, How Are You Going to Pay for That? remains a pleasure to read. Cooper recently left his correspondent position at The Week to become the managing editor of The American Prospect, an encouraging sign so long as it doesn’t lead to less written work like this book. As a one-volume comprehensive political education that’s easy on the eyes, Cooper’s book is one you won’t mind paying for.

Rob Larson is a professor of economics at Tacoma Community College. He is the author of Bit Tyrants: The Political Economy of Silicon Valley and Capitalism vs. Freedom: The Toll Road to Serfdom.