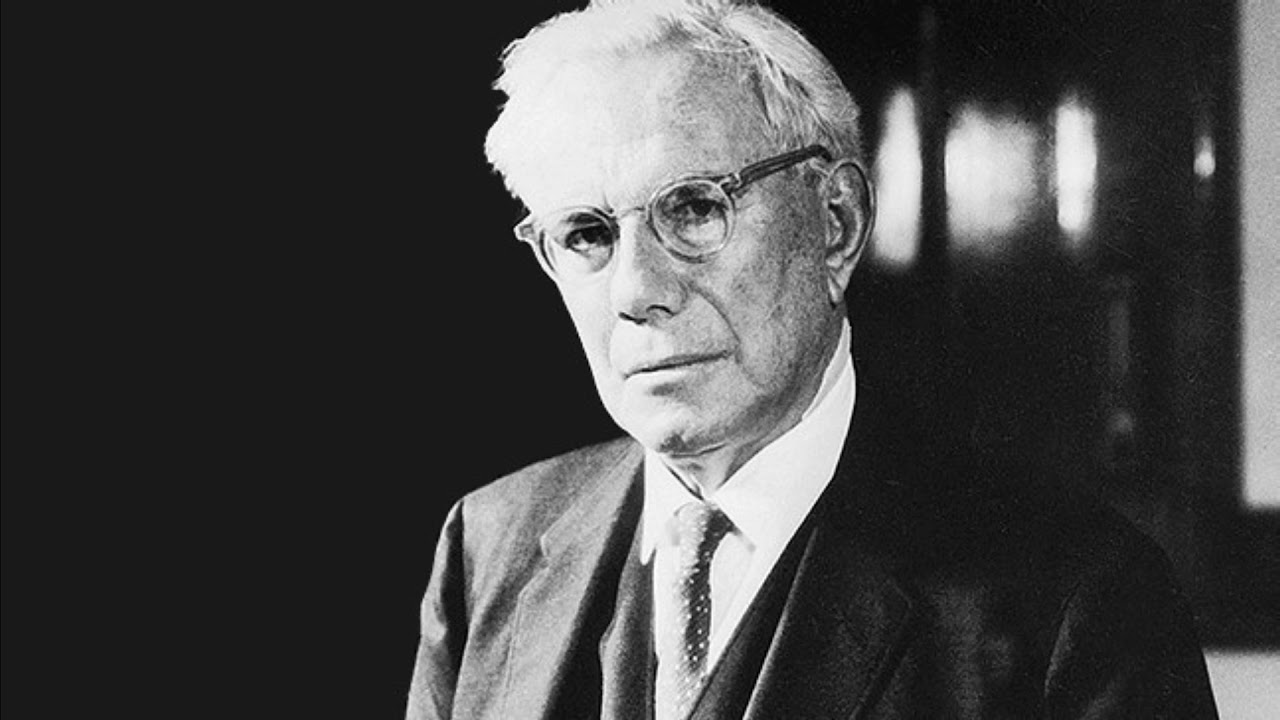

The German theologian Paul Tillich (1886-1965) is renowned today for his powerful synthesis of Christian theology and existentialism. He released an acclaimed series of short books written during the 1950s, including the evocative titles The Courage to Be and Dynamics of Faith. These texts laid out Tillich’s dynamic theology with a rare combination of economy and mystery, memorably describing “faith as a state of being ultimately concerned” and declaring that “courage can show us what Being truly is.” Later, he authored an epic three-volume Systematic Theology, which dove deep into the murk of existentialist philosophy, famously arguing that God constitutes the ultimate “ground of Being” implied in humanity’s search for self-transcendence.

While Tillich has become a veritable giant within contemporary theology, many are not familiar with his lifelong commitment to socialism, in both theory and practice. Tillich was active in Germany’s religious socialism movement and became deeply conversant with Marxist theory and politics. Notably, he authored a lesser-known book, The Socialist Decision, which argued for the necessity of socialism in the 20th century — and which he deemed his best work.

Socialism was no mere academic matter for Tillich. He served as a chaplain during the First World War, an experience that brought him face-to-face with the catastrophes of capitalism and militarism, as well as the political anemia of the Christian churches. He returned home to his native Germany, which was quickly turned upside down by the 1918 November Revolution. Kaiser Wilhelm II’s empire gave way to the cultural rollercoaster of the Weimar Republic, and Tillich and his second wife, Hannah Werner-Gottschow, embraced its social liberalism and experimentalism. They lived in an open marriage and frequented the avant-garde venues and social circles of the time.

Soon after the war’s conclusion, Tillich began to participate in working groups and intellectual circles with other religious socialists. In an early pamphlet co-authored in 1919, he urged “representatives of Christianity and the church who stand on socialist soil to enter into the socialist movement in order to pave the way for a future union of Christianity and the socialist social order.”

Then in 1932 came his book The Socialist Decision, written as the Nazis transitioned from a threatening political movement to a lethal political dictatorship. Tillich’s politics had already made him a liability for the Nazi party, and the book was immediately censored. He was allegedly offered a prestigious academic position on the condition that he repudiate the book and its criticisms of the new regime. Tillich laughed and was swiftly exiled to the United States, where he and Hannah lived out the remainder of their days.

The Perils of Political Romanticism

Though nearly all initial copies of The Socialist Decision were destroyed by the Nazis and the fires of war, a few remained in circulation among Tillich’s confidantes. Nearly forty years later, it was translated into English. The Socialist Decision is an underappreciated and highly unique contribution to the tradition of religious socialism. In addition to its theological insight, it exhibits great imagination and political sensitivity in dealing with the perils and contradictions of Tillich’s time. As waves of right-wing populism and illiberal movements crash against the institutions of democracy in the 21st century, The Socialist Decision deserves to be revisited and applied to our political moment.

One of the main targets of Tillich’s book is political romanticism, which he defines as a nostalgic attachment to a “myth of origin [that] envisions the beginnings of humankind in elemental, superhuman figures of various kinds.” This myth of the origin is one of the great “roots of political thought” and is the basis for all “conservative and romantic thought in politics.” Tillich discerned three basic origin myths that animate romantic politics: soil, blood, and social group.

These myths of origin help to sanction the present in two primary ways. First, they idealize a paternalistic past in order to “hold consciousness fast, not allowing it to escape from their dominion.” Second, they resist the demands of justice by freezing historical time into a recurring cycle of rise and fall. As Tillich writes, “The origin embodies the law of cyclical motion: whatever proceeds from it must return to it. Wherever the origin is in control, nothing new can happen.”

Myths of origin take on a special role in the wake of capitalism and liberalism, forming a bulwark against modern ideas of individualism, egalitarianism and the rational improvement of society. Such myths imagine a transhistorical founding of the people or state — one beyond questions of legitimacy and justice — that establishes strict hierarchies and naturalizes the existence of social classes. This mythical order depends on an elite few with elevated status and powers of rule over the underclasses; when the dominated classes attempt to deviate from this order, inevitable chaos and ruin follows.

Though Tillich was concerned mainly with the rise of Nazism, his analysis is highly applicable to 21st century conservatism. Origin myths are highly adaptable to different political and social circumstances, and are easily wielded by both religious and secular interests. For instance, many conservative Christians interpret human history through a pseudo-Augustinian lens of endless decline and fall. In effect, “nothing new can happen”: it is our fate to endlessly repeat the Edenic fall from grace, as virtuous religious societies emerge, fall into sinful permissiveness and decadence, and collapse in ruin.

Tillich’s metaphors of soil and social group, which emphasize a primal rootedness and connection, are clearly deployed by nationalists to instill a sense of organic belonging and imagined community. The culturally and racially homogenous nation is contrasted with a decrepit one, polluted by unrestrained multiculturalism and the presence of foreign aliens — those who are not “native” to the soil and become parasites on national culture and institutions.

The most insidious myth of origin, according to Tillich, is the “animal form of origin” or “origin of blood.” This myth embraces violent hierarchy and racial superiority, imagining a clash with other “animal powers in a process of selection through struggle and breeding.” Rather than describing the long fall in terms of grace and sin, or vibrant national culture and decadent decay, it invokes the starkly racial crises of genetic pollution and demographic decline. Today, the right increasingly relies on these tropes: right-wing figures like Charles Murray and Andrew Sullivan have re-popularized notions of “race science,” while Tucker Carlson breathlessly warns 5 million viewers about the impending breathless alarm “great replacement” of white voters.

The Conservative Uses of Origin Myths

Despite the varied and sometimes contradictory uses of these myths by the contemporary right, they all serve to rationalize a nostalgic attachment to a gloriously idealized past. Because the bogeymen of “liberalism,” democracy,” and/or “social justice” have severed society from its primordial origin, the present can be recast as merely a hollow shell. The modern revolt against political and social hierarchies have handed illegitimate power to the unworthy, the immoral and the outsider—a power they cannot capably exercise. And so, paradoxically, the conservative must fight to bring the past into the present. As Corey Robin memorably notes, “Conservatism is about power besieged and power protected. It is an activist doctrine for an activist time.”

This point is very important, as liberals and leftists often mistakenly assume that conservatism is primarily about the defense of the past. But in moments like Tillich’s, when liberal institutions are vulnerable and social movements threaten to upset the status quo, the reactionary response must be equally activist. In pivotal political moments, the conservative cannot be a crotchety defender of the status quo, since it has become clear that cannot halt the underclasses’ forward movement. Instead, conservatives must continually develop creative new forms of power to halt the decay of modernity and democracy — often by more effectively wielding the technological power and innovation that exploded in the modern era.

This paradoxical need to establish new forms of power by appealing to a romantic past easily leads to intense competition between conservative factions — both in Tillich’s time and ours. Tillich captures this conflict by distinguishing between “conservative” and “revolutionary” romanticism. Conservative romanticism “defend[s] the spiritual and social residues of the bond of origin against the autonomous system, and whenever possible [seeks] to restore past forms.” This kind of romanticism has animated much of modern conservatism, which usually tries to restore traditional forms of elite society by rolling back reforms, defending free markets, and neutralizing radical movements. In an American context, the “fusionist” project of combining traditionalist conservatism with laissez-faire economics is emblematic of this tendency.

But when liberalism threatens to be dragged to the left or traditional conservative elites, a more radical, “revolutionary” romanticism of the far right can emerge. Revolutionary romanticism “tries to gain a basis for new ties to the origin by a devastating attack on the rational system.” It brooks few compromises with political institutions and attacks traditional elites for their inability to order and purify the national community. Where revolutionary romanticism gains ground, it launches its devastating attack against representative democracy, first by strategically collaborating with traditional elites and then violently crushing them and all political opposition. This is precisely what happened in 1930s Germany, when the youthful Nazis entered into an alliance with traditional conservative nationalists — only to brush them aside once they’d served their purpose.

Liberalism and Socialism: Friend or Foe?

Tillich’s discussion of German liberalism and capitalism — both of which opened the door to Nazi reaction — is especially insightful for understanding our contemporary moment. Tillich was well aware that capitalism and liberalism arose as intertwined forces. Weilded by the capitalist class, liberalism was instrumental in severeing society from traditional religious and communal bonds and introduced the world to the horrors of colonialism, imperalism, and slavery.

But the fact that liberalism and capitalism developed together did not lead Tillich to a dismissive critique of liberalism. Unlike some contemporary Christian theologians whose “anti-capitalism” involves categorically rejecting liberal modernity or rehabilitating pre-liberal political ideas, Tillich insisted on the necessity of liberalism for the socialist project. He praised liberalism’s individualism, rationalism and moral egalitarianism as indispensable for authentic democracy and socialism. As he put it, “liberalism and democracy in fact belong very closely together. Each is at work within the other; and in spite of the sharpest tensions that may arise between them, they can never be separated.”

However, Tillich was highly critical of the bourgeois capture of liberalism, which granted liberty and self-determination to the capitalist class, and denied it to the masses. It was because the capitalist class had failed to “actualize the democratic demands of its own principle” that liberal political radicalism in the 18th and 19th century quickly gave way to abstract idealism. Tillich knew that liberalism could not be rolled back — this would be yet another romantic reaction. Instead, to truly realize the liberal promise, liberalism would have to be severed from the capitalist system that results in “total human objectification because of economic objectification.”

In our time, liberalism and capitalism have also come under intense scrutiny from both the right and the left. One notable criticism comes from a growing number of right-wing, largely Catholic intellectuals who have called for an end to liberalism. This cadre of “postliberals” contends that political liberalism has given rise to a tyranny of secularism, individual autonomy and transgressive identities. Because they believe that liberalism is inherently hostile toward traditional Christianity, postliberals have coalesced around a strong state (often aligning themselves with far-right politicians), fighting culture wars against “elites” and “wokeism” and rehabilitating a hegemonic “cultural Christianity.”

Unlike “fusionist” conservatives, postliberals regularly criticize free markets for their role in maintaining liberalism. However, it is not capitalism itself that unsettles them, but the pervasive market relations that threaten the “traditional” forms of social, sexual and religious life they wish to maintain. Inevitably, their softball criticisms of consumerism, markets, and Wall Street take a backseat to more pressing anxieties — for instance, who gets to use which bathroom, and the scandal of drag queen library hours. The free market is bad not because it subjects us to social and political unfreedom, but because it grants us too much freedom from our naturally “given” roles.

Though written nearly 100 years ago, Tillich presciently grasped how these social conservative revolts against market tyranny play a role in the reproduction of capitalism: “The apocalyptic pronouncements of doom which the intellectual groups of political romanticism direct at industrial society do not hinder the bearers of capitalistic power from using the new, supposedly anticapitalistic forms of social reconstruction to secure their own class dominance.”

Tillich also anticipated the political vision entailed in postliberalism: a combination of authoritarian capitalism and nationalism. Stark market inequalities will be maintained alongside a state that advances illiberal social policies and suppresses progressive movements — all in the name of preserving a unitary national identity. As Tillich put it, “the bourgeoise, with the help of the idea of the nation, succeeds in overcoming its political opponents at home, in enlisting in its service the pre-brougeois forces that are still bound to the origin.”

By contrast, Tillich offers a far more progressive account of Christianity that contains sharper anti-capitalist resources for the left. Unlike today’s postliberals, who want suppress liberalism — and the marginalized subjects who have laid claim to liberalism’s promises — Tillich knew that Christians must protect and radicalize the liberal legacy by deciding for socialism. He described this as the primary “internal conflict of socialism” rooted in the “internal conflict of the proletariat situation.” For Tillich, the true realization of universal equality and freedom could only be attained in a courageous decision for a liberal, democratic socialism.

This would require a decisive break from myths of origin, and their pessimistic politics of grandiosity and dominance, as well as a commitment to a more human future beyond capitalism. As Tillich put it “the breaking of the myth of origin by the unconditional demand is the roots of liberal, democratic, and socialist thought in politics.” How this could be achieved in theory, let alone in practice, is the immense task that fell to socialists then — and now.

What Comes After a Failed Revolution?

One complicating issue for German socialism in the early 20th century was its understanding of Marxism. Tillich adopted a nuanced, balanced approach to Marx in The Socialist Decision, neither praising him as a Biblical seer nor dismissing him for his “materialism” or “economism,” as Christian theologians often do. Tillich found a great deal of moral value in the young Marx’s critique of capitalist alienation, and extolled Marx’s mature theory of historical materialism. But he was staunchly critical of “dogmatic” Marxists in Germany, who claimed to have discovered in Capital a lithomantic crystal that foretold an inevitable socialist future.

Tillich noted that belief an inexorable socialist victory became a lethal hallucinogen to many movements, as they vested their hopes in calculating the moment of crisis and revolution. As these confident hopes failed to materialize, a morbid sense of disappointment set in.

The belief that history moved irresistibly toward socialism contributed to a tendency among German Marxists becoming detached from a materialist praxis bent on changing the world. Instead waging a relentless struggle to obtain power and enact socialist reforms, too many radicals gave into theorizing evermore elaborate predictive models capitalism would collapse under the weight of its own contradictions. In a grim turn, heated Marxist debates about forming a united front with “reformist” social democrats against fascism resulted in a Nazi waltz to victory. Marxist theory had dictated that fascism was little more capitalism’s dying gasp; instead, the Nazis marched social democrats and communists into the concentration camps.

There is another contemporary lesson to be drawn from Tillich’s analysis of German Marxism. Since the vulgar Marxist belief in the inevitability of revolution sputtered and then died, the contemporary left has fractured, and now spends a great deal of time mincing minute differences between social democrats, radicals, left-liberals, communists, Marxists — often in a needlessly puritanical fashion.

While conservatives happily seize on this (disproportionately online) phenomenon as proof of leftist intolerance, I hold a different view. As Ben Burgis and Natalie Wynn of Contrapoints have pointed out, much of this behavior is rooted in melancholia. Deflated by a sense of political impotence in the face of neoliberal, leftists increasingly turn to aesthetics, performance, and the cultivation of personal political brands.

Purity of spirit and staking out the most radical positions easily takes the place of the day-to-day work of engaging the masses and winning reforms that benefit working people. Small political achievements are deemed a distraction from revolutionary politics (both before and after they’re won). Fellow leftists who insist on more nuanced understandings of theory and practice are immediately told of the utter immutability of the systems of power and oppression we oppose. This dialectic of puritanical posturing and fatalistic resignation is one of the greatest obstacles to restoring hope among the left that “we have it in our power to begin the world again.” We should heed Tillich’s corrective to leftist melancholia, which invoked prophetic hope: “Socialism lifts up the symbol of expectation against the myth of origin and against the belief in harmony.”

A Prophetic Demand, a Socialist Future

Tillich insisted on making a “decision” for socialism, and developing the courage work toward achieving it. As the forces of conservative and revolutionary romanticism bear down on the 21st century, Christians and socialists cannot assume that the arc of history will bend toward emancipation without costly struggle and reactionary backlash. But this is no reason to retreat to a vulgar revolutionary optimism or melancholic puritanism. As Tillich observed, the superiority of the socialist principle is rooted in a “propheticism” that makes an “unconditional demand” on the present, rooted in a promised future. Tillich concluded in The Socialist Decision, “Only through expectation is human existence raised to the level of true humanity.”

No one expressed this truly revolutionary expectation better than Tillich’s greatest pupil Martin Luther King, Jr., who deserves to be the final word on this point:

“[T]he question is not whether we will be extremists, but what kind of extremists we will be. Will we be extremists for hate or for love? Will we be extremists for the preservation of injustice or for the extension of justice? In that dramatic scene on Calvary’s hill three men were crucified. We must never forget that all three were crucified for the same crime—the crime of extremism. Two were extremists for immorality, and thus fell below their environment. The other, Jesus Christ, was an extremist for love, truth and goodness, and thereby rose above his environment. Perhaps the South, the nation and the world are in dire need of creative extremists.”

Matt McManus is a visiting professor of politics at Whitman College. He is the author of The Rise of Post-Modern Conservatism and the coauthor of Myth and Mayhem: A Leftist Critique of Jordan Peterson.